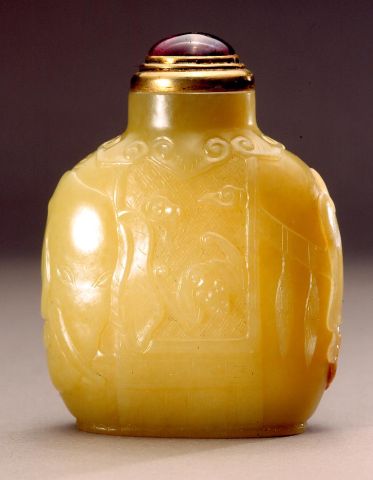

Bottle ID: 210

WITH ELEPHANT CARVING

Date: 1750-1799

Height: 68 mm

Nephrite of pebble material, the yellowish-green material with some pale yellowish-russet and brown skin; of very well hollowed rounded rectangular form with a cylindrical neck, concave lip and recessed oval foot surrounded by a broad, flat footrim, carved with a similar design on each side of a caparisoned elephant, its head extending onto the narrow side in each case, its trunk terminating in a Lingzhi shape, its saddle blanket falling the full length of the bottle with another Lingzhi shape close to its neck above a formalized brocade design superimposed with clouds and a bat in low relief terminating in a border of double-unit leiwen (‘thunder pattern’) and tassels.

Imperial, attributed to the Palace Workshops, Beijing.

Similar Examples:

Crane Collection nos. 169, 220, 256 and 326

Moss, Hugh, Victor Graham and Ka Bo Tsang. The Art of the Chinese Snuff Bottle - The J & J Collection, 1993, Vol. I, pp. 81-81, no. 32.

Moss, Hugh, Victor Graham and Ka Bo Tsang. A Treasury of Chinese Snuff Bottles - The Mary and George Bloch Collection, 1995, Vol. 1, pp. 48-49, no. 15 and pp. 106-107, no. 41.

Provenance:

Hugh Moss [HK] Ltd.

The Imperial designation here is based upon a variety of factors. The elephant was a popular design at Court for a variety of wares, with Buddhist connotations probably providing the main impetus. In the Imperial Palaces elephants are frequently found in pairs supporting various symbolic objects or in their own right and set on tables, altars, etc. The transformation of the elephant to serve other symbolic purposes is typical of Imperial production where a large quantity of bottles was made either as gifts to the Emperor or gifts from him, where longevity, happiness, ample progeny and other symbolism was appropriate. This is found here in the termination of the elephant’s trunks in Lingzhi symbols, implying that the recipient attain whatever is desired (the ruyi symbolism of the Lingzhi head) and enjoy extended life (the longevity symbolism of the Lingzhi), and in the flying bats superimposed upon the saddle blanket (happiness symbolism). The elephant also became a popular form for snuff bottles during the mid-Qing period, with a number of them made in glass, many Imperial yellow, also attributable to the Court.

Another Imperial connection is with no. 32 in the J & J Collection (Moss, Graham, Tsang, The Art of the Chinese Snuff Bottle). This unquestionably Imperial bottle, with its ‘Imperial command’ designation in the mark, is of similar material, size and form to the present example. The comments on the J & J bottle as to provenance are all equally applicable to this one.

Quite independent of its likely Imperial status, this example is of extraordinary quality in the choice and use of material and in the workmanship, with carving and detailed finishing better than which it would be difficult to imagine. It is also superbly hollowed, even better so than the J & J example, with a beautifully carved concave lip, another feature in common with the J & J bottle. Although almost certainly of the Qianlong period, the size of this bottle might suggest a date from the second part of the reign when, apparently, larger bottles came into vogue. This would also accord with the dating of the glass bottles made entirely in the form of elephants with howdahs on their backs, which appear to be a development of the mid-Qing period and not to predate the latter part of the Qianlong period at the earliest. With the growing interest in snuff bottles at Court during the Qianlong period and the need to constantly revise designs to satisfy Court taste, which presumably became jaded rather rapidly with the vast resources at its disposal, it is likely that new designs would evolve by first using elephants as a design on bottles, then, as in this case, blending the elephant into the bottle so that the form is ambiguous, and end up at the point where the elephant became the snuff bottle form.

< Back to full list

English

English 中文

中文