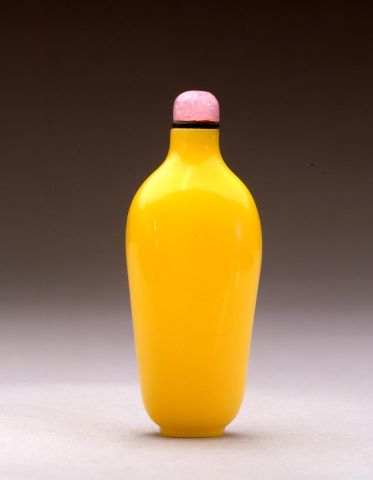

Bottle ID: 00266

YELLOW IMPERIAL, SLENDER, ELONGATED

Date: 1723-1750

Height: 58 mm

Glass, of flattened slender elongated form, with shoulders tapering to a long neck with a wide mouth, of opaque yellow tone.

Imperial, attributed to the Palace Workshops, Beijing.

Similar Examples:

Moss, Hugh M. Snuff Bottles of China, 1971, p. 105, no. 182.

Sotheby's, London, June 7, 1990, lot 268.

Sotheby's, Hong Kong, November 1, 1995, lot 809.

Provenance:

Clare Lawrence Ltd.

Alexander Brody

Clare Lawrence Ltd.

Joseph Baruch Silver

Y. F. Yang Ltd., 1981

Exhibited:

Annual Convention ICSBS Toronto, October 2007

Hololulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, Hawaii, November 23, 1989 - January 7, 1990

Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel, 1987-1988

Published:

Lawrence, Clare. The Alexander Brody Collection of Chinese Snuff Bottles, 1995, p. 70, no. 105

Brody, Alexander. Old Wine into Old Bottles: A Collector's Commonplace Book, 1993, pp. 86 and 149

Chinese Snuff Bottles from the Collection of Joseph Baruch Silver, in Conjunction with the Exhibition at The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Winter 1987, p. 9, no. 3

One of the important colors in the Qing period, and specifically until the end of the eighteenth century, was opaque yellow. Yellow was the color bound by Imperial regulations and restricted in its usage to members of the Imperial family. The Archives from the Zaobanchu mention opaque yellow as early as 1702 and it appears that different tones of yellow were used in parallel, being designated for specific members of the royal family. While the Yongzheng Emperor favored a more lemon-yellow, the Qianlong Emperor preferred a bright clear yellow.

One of the most fruitful areas for researching yellow has been in Chinese textiles. During the Qianlong Emperor's reign, the style of official Court robes became an issue and in 1766, the Board of Rites published an illustrated book of sumptuary laws, which imposed restraints on overindulgence at the Court. This voluminous tome was entitled the 'Huangchao li qi tushi', ('Illustrated Regulations for the Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Qing Dynasty'). It was compiled on the order of the Qianlong Emperor, setting out elaborate rules and specifications for life at Court, from the form of sacrificial vessels to ceremonial accessories and official Court dress. In 1759, the Emperor issued an edict setting out the conventions of Court attire strictly classified in accordance with the wearer's title, rank and status on which this work is based.

Several years after the looting of the Yuanming Yuan (the Summer Palace) in 1860 by the British and French forces, a number of original folios of the Regulations appeared at an auction in London, and were subsequently acquired by both the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Chester Beatty Museum in Dublin and among others. The rules for the use of yellow are specified very clearly and show how important the folios are as they provide visually accurate information about the colors that the eighteenth century Court were permitted to use.

During the Qianlong era, it appears there were at least four different colors of yellow designated for Imperial use. These are as follows: Ming huang (bright yellow), Jin huang (golden yellow), Xiang se (incense yellow), and Xing huang (apricot yellow). Ming huang was reserved for use by three people: the Emperor, the Empress and the Empress Dowager. Although the Emperor wore other colors such as blue and red on differing occasions, this color could not be worn by anybody other than this illustrious trio. From the folios, there are a number of examples referring to this color. Jin huang was reserved for the use of the Emperor's sons (the Imperial princes) and for the 2nd and 3rd degree Imperial consorts. Xiang se as a color was used by the Imperial consorts of the two lowest degrees, the Emperor's daughters and the wives of his sons. The last color, Xing huang, was the most unusual of the four colors and was reserved for only two people - the Crown Prince and his Consort.

The Illustrated Regulations are not limited solely to the description of Imperial costume but also to specifications of many objects for use in the Court, including for example, ritual vessels, musical instruments, banners and, of course, ceramics. An observation of bowls with Imperial reign marks also show the differing tones of yellow described above. There are no examples of snuff bottles in either the folios or the Illustrated Regulations. One would not expect them to be listed, as snuff bottles were never included in the formalized rituals and ceremonies of the Court. The taking of snuff was a leisurely pursuit and although the social rituals attached to this were universally accepted within the Court, they were never formalized to be included as part of the ceremonial paraphernalia. Where the overlap would have occurred is in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries through the use of yellow. Only members of the Imperial family, if they took snuff, would have owned yellow glass bottles.

< Back to full list

English

English 中文

中文